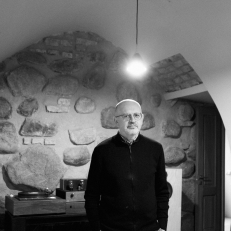

Antanas Sutkus, born in 1939, lives and works in Lithuania. At the end of 1950 he was one of the founders of the organisation Photography Art Society of Lithuania, and left his mark on the classical photographic climate with his still ongoing series of pictures People of Lithuania, which documents the revolutions the country experienced during the 20th century and up until today.

Today his work is to be found within the international collections such as National Library of France, the Art Institute of Chicago, International Center of Photography in New York, Dresden State Art Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Swedish Moderna Museet.

Florian DAVID: What are your views on our present world?

Antanas SUTKUS: The world is ugly.

DAVID: Tarkovski said that the artist exists because the world is not perfect.

SUTKUS: I would absolutely agree, however I would like to expand on this thought: art exists not just because the world is not perfect but also because man is not perfect. And the arts must help Man become better. In the field of science we have achieved “cosmic” results over the past 2000 years. Yet if you consider people, their relationships, the human’s soul – we are not very different from the people living at the time of the Roman gladiators…

Art alone will not solve at once all of the world’s problems. It can only affect you as an individual, and it is then up to you, once you have been touched, to make the world a better place. Only through politics, and journalism can you make a real impact on the world, you can point to certain things, you can denounce genocide, and influence the process…

DAVID: What do you mean by making the world ‘better’?

SUTKUS: The world has to become a better place, now it is very imperfect. So we have to make it better. There is so much hunger, so many people, children especially, are starving, there is such a huge social divide…Then look at Europe and this Ukrainian conflict. European countries are still selling weapons used by Russia-backed separatists. And I think that if Europe will not understand that morality is not less important that business, it will collapse.

DAVID: Don’t you think that Europe has collapsed already?

SUTKUS: I think that now is time for Europe to make up their mind… Is it business or morality…I think that Europe is on the edge of collapsing… Right now Europe is like a rabbit paralyzed by a boa… The boa hypnotizes the rabbit, and Europe is shying away (from its responsibilities), not responding. Europe has not nurtured any leaders. Mr. Obama is not just the leader of the USA, he is a (global) leader strong enough to engage with Putin. Europe does not have anyone to engage with Putin.

DAVID: Where were you born Antanas Sutkus?

SUTKUS: I was born in a village. Not far from Kaunas, in a village called Kluoniskes. My dad was a representative of the left-wing but he did not agree with the Bolsheviks’ line… and in October 1940, he shot himself. And he was 28 years old…This is where my love for neo-bolshevism comes from…

DAVID: Did you resent the Soviets because of this? How did that affect your work?

SUTKUS: This has affected not just my work, this has impacted my whole life.

DAVID: What kind of a kid were you? Were you already interested in photography? What kind of childhood did you live?

SUTKUS: I remember that from around 5-6 years old, I fell ill with tuberculosis…Which at the time there was no cure for. I was reading a lot. I read all the books in the local library! And also all the yellow literature (the forbidden) that our neighbours had…

DAVID: Do you remember precisely what books?

SUTKUS: I started maybe with 'Winnetu’ by Karl May, Ziulis Vernas, Hugo etc…Then the Russian writers: Tolstoy, Ivan Turgenev, Nabokov…

DAVID: Do you remember your first camera?

SUTKUS: Maybe when I was 13-14 years old. I had three dreams then: getting a camera, a bicycle, and a radio. So the bicycle I tried to make myself, but the wheels turned out square! During my summer holidays I used to work in a peat pond, and this is how I earned money to get a radio and a photo camera. I needed the radio to listen to “Radio Free Europe”, “The Voice of America”, well… those secret, banned stations. So from the age of 6, I could already speak and read in Russian, because all those foreign programs only came in Russian. You only had to make sure you closed windows and doors well, so no one could hear, because this was forbidden. And sometimes people used to come to check if you were not listening to something forbidden…

DAVID: On August 1965, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir went to visit the USSR and made a stop in Nida. You documented that trip. How did you manage to be a part of this trip?

SUTKUS: At that time I was friend with the Writers Union leader Eduardas Miazelaitis, who organized that trip. He invited me, but the Central Committee did not really want to approve my attendance, because I was too 'bohemian’, too 'unpredictable’, 'too free’.

DAVID: What had you done to be considered not reliable enough?

SUTKUS: Well, I was living a very active life, I was reading books that were forbidden. We were talking, discussing arts and literature. I was living a free, independent life… I was not openly against the Soviet Government, but sometime I would tell a joke about it.

DAVID: You were 26, you had read all Sartre?

SUTKUS: Well yes, I was reading a lot. Two years before meeting Jean Paul Sartre, I had to stay in a sanatorium. So had I read all the French and American literature and everything that I could get my hands on. I had not read anything of Simone de Beauvoir, but Sartre was one of my favorite writers, and I was very much interested in the American writers, so all these days while Sartre and I were having breakfast, lunch, or dinner, we were talking about literature. I was so surprised how Sartre, a Nobel prize winner, could chat so simply with such a “small fry” like me. The last evening of the trip, we stepped out with Sartre for a cigarette. This is when he asked me what I was writing: 'prose or poetry?’ - I answered him: 'I am not writing anything, I am a photographer’. And so he then said: “Oh my god, I only let one photographer take pictures of me, and that is Henri Cartier-Bresson. But it is the last night so I won’t kick you out. At least promise me to post me the photos.’ 'Ok, I will send them’ I answered… Sartre’s lover,Lenina Zonina - the trip translator - was then living in Moscow, so I sent Sartre my pictures through her. She later told me that during a party Sartre was showing those pictures to his friends, and that he was very happy about them.

DAVID: Did you already know Lenina Zoniva?

SUTKUS: No, they arrived altogether: Lenina Zonina, Simon de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. Lenina Zonina was a translator of Sartre’s books from French into Russian. She was ideal, a very good translator.

DAVID: Do you know if she was also working for the Soviet Government?

SUTKUS: I am not exactly sure what she was doing. Maybe she was also working for the secret services. But from what I gathered, they tricked the secret services, because Lenina Zonina, Sartre and the former French culture minister used to write some reports in the basement of the embassy.

DAVID: This work of Sartre and de Beauvoir feels extremely intimate, nearly metaphysical. Did you go into that job with a specific objective in mind? What did you want to achieve?

SUTKUS: I simply wanted to take interesting pictures of those two guests that were visiting Lithuania. Good photos. And somehow I managed to do it. Now in the USA there is an exhibition about this visit. Around 70 pictures are exhibited.

DAVID: What do you mean by 'interesting’?

SUTKUS: Good photos. Best in the world photos. Unique photos that someone else would not have taken. Sartre and I had a great connection. Also he did not pay attention that I was taking pictures of him, my camera was very modest and he thought that I was a writer. We were mostly enjoying ourselves and chatting about literature. He was surprised that I knew so many authors that were not yet well known in the Soviet Union. I was not introduced to him as a photographer. I was together with the family of Miezelaitis, with his son and his wife. It was not up to the government to decide my attendance, it was the Central Committee and the minister of culture of the times, Sepetys, who let me attend.

DAVID: In 1965, Sartre was at the height of his glory, he had just refused the Nobel Prize. This trip in USSR was an important moment. Did you feel that you were capturing an important event?

SUTKUS: For me Sartre’s literary works were more interesting than the man himself. But he came across as a very friendly person, direct, someone affable with whom it was interesting to interact. We were chatting all the time, not about his own works, but about the Americans, the existentialists, about Kafka, Joyce, Camus, all the other writers.

DAVID: Let’s talk about your other works? I read that there are today more than 700,000 pictures of yours, is that true?

SUTKUS: 100,000 I think. They will count after my death! This exhibition gathers works from negatives we uncovered over the past five or six years.

DAVID: Till 1969 you were into photojournalism, and you then moved into 'independent photography’, why?

SUTKUS: From 1969 I was a board-member of the Lithuanian Photographers Society. But journalistic work was not the kind of aesthetic, artistic work I wanted to do. Also during my time with the Lithuanian Photographers Society the censorship started to become much stronger, and a lot of pictures that I took had to stay in my drawer. I could not exhibit them.

DAVID: You work exudes tenderness for your very own people, and at the same time there is a level of detachment that could be that of a foreigner. You are managing to be like a foreigner in your own country. How do you manage to reconcile those two visions?

SUTKUS: It is very ice to hear that my approach is from the side. I would like to hear this more often! I am taking pictures like a simple person. Not as a photographer. Just like a stranger who passes by. I guess my photography is humanistic. Tenderness, kindness and warm relationships, purity, love, have been the most important things throughout my whole life. This is why this is what you see in my pictures.

DAVID: How about your method. Do you shoot from the hip or do you ever ask people to pose? I am thinking about this beautiful woman at the balcony, for instance?

SUTKUS: No picture I took was ever staged. Never. There is no posing. There is communication, interaction with people.

DAVID: There are two of your pictures that I particularly love. One is a woman standing over a balcony looking down the street, the other is a kid with big eyes untitled 'Pioneer’. Can you tell us the story behind those two pictures?

SUTKUS:In 1962 a publisher commissioned a book about the deaf and blind children school in Kaunas, so I took a lot of pictures and this kid is part of that series. He was a blind pioneer from that school Unfortunately, at the time It looked too 'Soviet’, and so I could not show it anywhere. I only showed that picture after Lithuania had declared its Independence.

DAVID: Do you remember that kid’s name?

SUTKUS: No… I never remember any names, otherwise I would need to remember half a million people’s names!

And the ’Marathon’ picture was made on a balcony. This is a picture I took in 1959. I was a student, this is a picture I took from my dormitory room. My lover from university was looking down (the street). I saw an interesting shot, so I asked a few friends to tie my legs with their belts and to hold me above the street. I only got about 10 seconds to take this shot, not more. I snapped maybe three or four times, but I could do no more, else they would have dropped me onto the street!

DAVID: Do you remember the name of that girl?

SUTKUS: Her name was Irena… I remember her surname too. Oh…it was a big romance…We were both 20.

DAVID: Thank you Antanas Sutkus.

SUTKUS: Thank you.

His most recent book - Antanas Sutkus – People of Lithuania is a new book showing a selection of his photographs.

Published 2015 in a cooperation between Antanas Sutkus, Kaunas Photography Gallery and the Lithuanian Photographer’s Association.

Add a comment