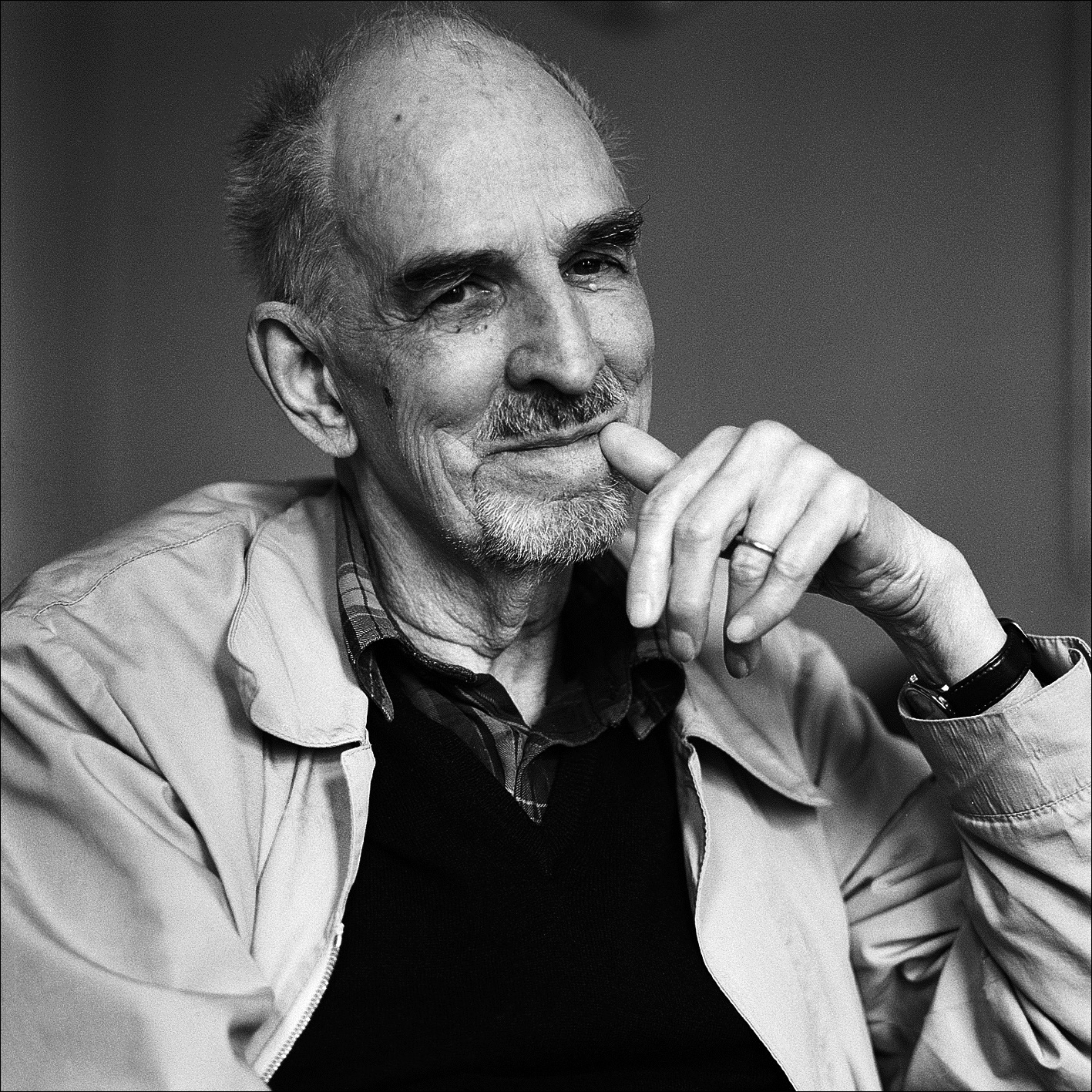

Above featured: Swedish Director Ingmar Bergman. Dramaten. Stockholm , 4 IV 2001, by Hasselblad World Master Award Winning Photographer Frederick-Edwin Bertin (The only other photographer with Irving Penn to have ever photographed the Master).

Florian DAVID: Good morning Frederick-Edwin Bertin! You are now in New York, back from a quick trip in Paris. How are you feeling today?

Frederic-Edwin BERTIN: We are great thank you! It was fast yes but we are used to it! We met many great people in Paris amongst which Louis Benech! There are not many people like him left!

DAVID: Looking at you I cannot explain why I have this feeling that you belong to another time, is that how you feel too?

BERTIN: Many people tell me this! I know that my education was a bit out of the ordinary, not necessarily in accordance with our times, yet I still feel a man of my century, I do not want to be a man of the past.

DAVID: Let’s start with your name is Frederick or Frederick-Edwin your first name?

BERTIN: Frederick-Edwin is my first name.

DAVID: Where does it come from?

BERTIN: Edwin was a nephew of my father and also my godfather, I only met him twice and I do not even remember him. He was of Irish descent, his name was Ashworth. Funnily, besides my father another very important person in my life was a good friend called Florian, who had attended Saint-Cyr with my father. He was very kind and knowledgeable he played a major role in my education. Florian Prieur de la Comble - his mother was a Choderlos de Laclos, and his father was related to the writer of Les Liaisons Dangereuses ('Dangerous Liaisons').

DAVID: Where were you born?

BERTIN: I was born in a very small village in Seine-et-Marne sixty kilometers from Paris, it used to be only forests and fields, it’s called Romaine, near Lesigny.

DAVID: Do you have a large family?

BERTIN: I have a very small family. My father was the last child of a very large family, born after World War I, and all his sisters and brothers were born before World War I, he was a lot younger than them, and so my cousins are much much older than I am; so I was a single child but on top of that I did not really met and played with my other cousins. I was very much by myself, it felt a bit lonely. My parents traveled a lot and every holiday abroad we visited the capitals of Europe and museums, and so I got quite knowledgeable early on about history and the arts, which meant that at school I was looked upon as a quite a strange fellow! [laughs]

DAVID: Your father was a meteorologist?

BERTIN: Yes. But he was also extremely knowledgeable in history, in geography, in architecture…In the same morning we could have conversations about Churchill and World-War II, Shakespeare, and then go on to discuss Jefferson or Houdon! These were our regular conversations initiated when I was barely ten years old! [laughs].

DAVID: Where did he get this appetite from?

BERTIN: Well he was a man of books. Before going to Saint-Cyr he was reading and speaking Latin and Ancient Greek fluently. His parents sent him to Saint-Cyr, which was not necessarily what he had been wishing for. His mind accepted it eventually but I think that his body resented it. He was forced to go to Saint-Cyr just before the war. He didnt like uniforms, he was a rebel in his own way. He was a free spirit. In 1942 he fled to Alger. At the time de Gaulle banned ‘Vol de Nuit’ by Saint-Exupery and my dad for instance found the book and read it in one night under a lamppost. A way to affirm his freedom.

DAVID: Do you think that this is a value he wanted to pass on to you?

BERTIN: Definitely, he had this desire to pass on to me everything that he knew. He liked to share with his son everything that he loved, appreciated, and what he thought was good for me. Dad had accumulated a fairly sizeable amount of books, a proper library. He always said that this library was the best tool to raise a gentleman. When he passed away a friend once asked me what dad had left me, and I was quite shocked by this question. I answered her, I said that he left me five-thousand wonderful books from his library, and I heard her little voice answer: ’is that all?’. But in these books, there was everything.

DAVID: Are these books now in your flat?

BERTIN: Yes, not all of them at the same place.

DAVID: Do you often go back to them?

BERTIN: Not as much as I wish. But I know exactly where they are.

DAVID: Let’s return to the beginning of our chat with you? You describe yourself as a traveler from the 18th century to the 21st century with your cameras. Can you elaborate on this, why do you feel that way? Is there any particular time even a specific year during which you would have liked to live? Other than the 21st century?

BERTIN: I am a man who essentially looks and observes. I am not judging my own time. Sometimes I feel that people, and women, are not dressed as well as they could be [laughs]. I find women are not as elegant these days as they were during my childhood, except for my wife [laughs] - joke aside, I find sometimes that the way that people dress today is not very attractive, not photogenic. To give you another illustration, I spent a part of 2013 in Monaco on an assignment and the ugliness of the place made me very sad, to the point that I got sick. The volumes of that city’s architecture are not something that I understand visually. In contrast to New York however which modernity I find makes it a beautiful town, and where I feel at ease. Urbanists have managed to create a certain harmony, and I need this harmony to be happy. I feel that people today no longer dress with harmony, there is a certain ugliness to our civilisation. You see beautiful women with torn apart jeans. Otherwise I like my times, they are interesting, and they are mine.

DAVID: What do you like in our times?

BERTIN: What I like is that there are so many people doing so many amazing things; people who create every day and invent new tools, medicines, who allow us to live better, more safely, to fight diseases which used to be lethal years back - I am thinking of my mother who had been suffering from Parkinson's disease, and I think that this disease in twenty years will have its cure, this is wonderful. Seventy years ago you could die from tuberculosis, today this is over. These people could be my neighbours, but these heroes are the most unknown. One of my big subjects was an immersion within Cambridge University where I met charming people, full of humour, who did not take themselves on serious and welcomed me with the utmost simplicity and kindness. They guided me through some of their discoveries in such a simple way as if we were going hunting for flowers. And these personalities are totally unknown. Our reality-shows culture sheds too much light on people who are deplorable and have achieved nothing substantial in their lives. And in fact this has to be what I like least in our era. People do not like their time because they do not even know that these other formidable people exist.

DAVID: Do you think that we need mentors in life?

BERTIN: Absolutely, religion is no longer impacting people’s lives as was the case fifty years ago, and the same holds true for politics, as well as the ideologies of the twenties and thirties, they were not the right ones - so to compensate a lot of people are filling this void but are doing so with false references. During the Renaissance Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were considered superstars, however they had an obligation to explain their work to the people they encountered on the streets, they were mingling with people! Today if a simple man in the street tries and asks the most famous painters or rappers what are their next projects, I am not sure that they would treat this man kindly, when in reality these artists’s works will certainly not have the same impact as La Pieta or The Gioconda! Leonardo Da Vinci was one of the most charming men on earth. So for someone like me who observes things, we live both in extraordinary and not so extraordinary times…

DAVID: Do you believe there is a loss of culture?

BERTIN: Yes a loss of culture. When paradoxically we have never had so many opportunities to access knowledge. I think it is more a lack of curiosity from the younger generations, especially about what took place in the world before they were born. I often hear ‘but the man you are talking about is dead’…I say ‘yes’, then they say ‘Ha, then I am not interested’! Yes the man may have disappeared, but has left an importante contribution. This is what I learned from my father, and this has helped my inner peace.

DAVID: I think as pedo-psychiatrist Dr. Aldo Naouri explained quite justly, there is a lesser important role of the fathers today, who before were embodying authority and transmission. This might partly explains the loss of transmission.

BERTIN: True. We can no longer even correct our own children [laughs].

DAVID: Well it is about teaching respect and the notion of boundaries. This does not happen through violence [laughs].

BERTIN: Respect is not taught anymore. I think a kid can understand a small physical correction. As I often say I was raised with a Spartan father and a Lacedemonian mother! [laughs]

DAVID: Something intrigued me the last time we chatted briefly. You told me that your mother - to the contrary of your father - never trusted you. I would love to know more about this. Why is that?

BERTIN: Dad started trusting me when I was five years old. Not sure why. My mother had for everyone around her a very high level of expectations. You had to provide mother every single morning with some evidence that she could trust you. Whatever you had done the previous day or week was over. Sometimes I was finding this a bit difficult and painful. Of course she did not really like the fact that I became a photographer. A sculptor friend of my father - his name was Gustave Pimienta - was saying that you had to discourage a career in the arts. Life as an artist is so difficult that you must be very tough and strong-willed to do anything with arts, be you a sculptor or a painter or a musician, you need a lot of strength. So in a way my mother discouraging me was a good thing. If you are getting discouraged by the smallest things you do not deserve to go further. But if someone discourages you harshly and in spite of this you press on, then maybe you deserve to become one. This was difficult with my mother, as she stopped talking to me for three years. But Then when she realised that I had the will to press on in spite of her opposition, she started to understand.

DAVID: You regained her trust again

BERTIN: Yes!

DAVID: What drives you in life, where does your life force come from?

BERTIN: This is a good question actually. I love my work I really really love my work. I really love to think about what I will do and the way I will do it. I love to read and look at photographies. I really love to compose a photograph. I love to take portraits. It is not always easy because you can make thousands of portraits and still be as poor as Job, because people do not want to pay for them [laughs]. But I really love to look at people and eventually photograph them. I think that is my fire.

DAVID: Freud said that the child is the father of the Man it will become (‘L’enfant est le pere de l’homme) : have you today taken the whole dimension of that reflexion as far as you are concerned?

BERTIN: It is very lovely what you say Florian, because when dad passed away the priest who made the sermon that day gave me an amazing strength. Dad passed away in very strange circumstances, so I went through three months of a very bizarre situation and the priest said something to me. He said ‘Frederick, you are fine because you have become the man that your father educated and he will always be there with you because you were the purpose of his education. So in a way he is there with you.’ And this literally put me back on my feet.

DAVID: How old were you?

BERTIN: In 2006, I was 46. But dad was very important to me. We used to spend our lives together, we were seeing each other very often and talking, and going to exhibitions, museums, and suddenly he decided to take charge of his own destiny and I was not there. And this priest said the magic words.

DAVID: Are you a religious person?

BERTIN: I was raised Catholic, I went to Stanislas in Paris. There are two Bishops in my family, but I have my own way to be Catholic. I don't necessarily believe in an after-life, I believe however that we have to be good now. One has to be a fine man in this world. When I was at Stanislas one day I asked the priest to tell me where Jesus said that there is a paradise, and he could not find where! [laughs]. You have to be a good man now on this earth, not because you might get a reward one day and live a good life somewhere else. You have to be a good man to your neighbour, to your wife. I do not need nor want any compensation for this. I am a good man simply because it makes me feel fine in my own body. Everyday. Sometimes I can get stressed and jumpy to some people, and this makes me sad because I know I should not have behaved so badly. So I really try every day to behave well, not awaiting anything in return. This is a personal need for me to be kind to the people living around me, especially my wife because we live together, that is the most important.

DAVID: What is your definition of love?

BERTIN: It is to live in harmony with someone every day of our life. I met my wife very late, she as well met me late. We did not have real relationships before and so we know the value of this relationship and of being together. Love for us is harmony. Harmony while doing extraordinary things as well as very simple things. We never have any arguments, we do not always agree but we are always listening to each other and I think that this is the start of harmony. We listen and we are cautious so as to anticipate the other’s desires. With Marie there is no competition, it is not a soccer field, we are not trying to show our muscles, we are together listening to each other. What is wonderful in America, and that is the case with Marie, she helps me believe in myself, which is not something I was used to in France at that level. That someone would love you yes, but that someone would trust you so unconditionally, this is something quite formidable and appeasing, soothing. Not a confidence booster that makes you want to go overboard and ‘break everything’, no, on the contrary, it is soothing and helps preserve that trust in you to become even better - by that I mean not just professionally, but a better person towards the people around you. And I must say, for such a huge city as New York people are behaving here in a surprisingly positive way.

DAVID: Harmony is a beautiful word. It is friendship at its best.

BERTIN: Yes, friendship at its best, and also I think we are intelligent knowing how lucky we are to be together. And so we do not take this for granted. We live a remarkable life together. We have other desires of course, but we already have something there that we love very much. Every day, every moment we know the luck we have of being together. With Marie we realize too that we had a similar education, and when we speak about American or European history, we are understanding each other. If we speak about Louis XIV we do not have to explain the historical context.

DAVID: Doesnt it feel good to be understood?

BERTIN: Yes, it is very true. Even the decoration of our flats in NY and Paris we do together. It is an intelligent relationship. Harmony is the answer to many things in the world. It is also the answer, say, to doing a portrait. But people seem to lose sight of this. Today people want to shock. I was telling a friend today that in our XXIst century the best way to shock is to be classical. Everyone seems to want to shock, you see it in music, in fashion, in photography or the arts. But shocking does not mean anything anymore as we have been so far already. What can come next?! What is the next picture of Andres Seranno that could be more shocking?! I think the best way to shock today is to be classical.

DAVID: I think that Bergman would be very shocking to many who do not know his movies today.

BERTIN: Absolutely he would be extremely shocking.

DAVID: Yes I recently rewatched Summer Interlude (’Sommarlek’), and I was shocked indeed! [laughs].

BERTIN: Yes that one is stunning. The story of a ballerina who remembers her youth with a lover. It is so elegant and the story is so very strong!

DAVID: There is even a sex scene like you do not see any more these days. I thought it was very daring what he did there.

BERTIN: I think the Swedes have always been a bit of pioneers, ahead of the rest of the pack. They avoided two World Wars! I remember as a child attending a first of May celebration in Stockholm, and a left-wing demonstration was taking place: all these people were so neatly dressed, even their red flags were very carefully rolled up in a kind of beautiful exquisite leather tube! They were taking them out with great care, and then when all was said and done, folding them back very delicately in anticipation of next year’s demonstration! Only Swedes would do this! [Laughs]. Such an elegant demonstration, and then going back home maybe for a beer. A different country!

DAVID: I find interesting that you were five years old and that you paid attention to this and remember this from attending a political demonstration…

BERTIN: I have an amazing memory yes, for facts as well as perfumes. I can remember a place by its perfume. It is a bit like some drawers in my head.

I am actually beginning to write about all this.

DAVID: Can I ask, so you were 17 years old when you got this terrible virus which attacked your cornea, and is it in that hospital that you discovered Bergman?

BERTIN: No my parents already adored Bergman. However they always thought that it was more for grown-ups, so I was not going along with them. And when the man in the hospital in charge of the little movie-theatre there mentioned Bergman’s movies to me, I said yes of course, I would like to see them! He only had the ones before 1960. So I said why not! And he had to set -up everything because these were the old 35 mm copies you know. He was not even sure where they were! Then he fetched them and I went down, and a few friends of mine came along. This hospital was so incredible and everyone was so kind that there was a club of alumni from the hospital! We were like a little family. I was able to see all these pre-1960 Bergman films!

DAVID: So you saw these movies and decided that you’d become a photographer. Why didn’t you think of becoming a filmmaker rather?

BERTIN: No. I think I am a man of still photography. Even if I love David Lean so much - I think I have seen Dr Zhivago and Lawrence of Arabia at least a hundred times each, I know the dialogue by heart. To be a film Director you must be a General, you have to know how to give orders to your crew. These films are the medium through which I re-discovered the world after my blindness. I saw the world again thinking ‘ha this is how it is’! What really happened is that one afternoon I went out with a nurse and we headed to Hyde Park. It had rained all morning and all the leaves were sparkling with the light of the sun, it was autumn and it was remarkable. That day I decided to become a photographer.

DAVID: You like more the solitary aspect of your craft?

BERTIN: Exactly. I have been a man on my own for a long time - before meeting Marie of course - and this is the way I like it.

DAVID: So you were first exposed to Bergman’s movies while at the hospital. When was the idea born inside your head to go and try to capture a portrait of Bergman the man? (a task many other photographers endeavoured and failed at!)

BERTIN: What happened is that the man had haunted me for a long time. But first I went on to work for Vogue but after eight years, the Conde-Nast team changed completely and I decided to pursue my own projects. I went to Cambridge for a three year journey where I photographed everyone from the scientists to the gardeners, the doormen, the teachers and eventually even the students.

DAVID: It was not a commission?

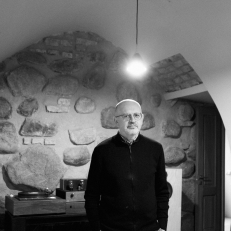

BERTIN: No I was my own producer, photographer, and assistant! I did it all by myself. And then I met someone at Christies who told me that it was a strong work but that doing something similar within the world of cinema would certainly deliver a stronger impact. So with my father we spent a few days brainstorming, thinking about what could be done. And suddenly we realized that a work on Bergman would be a fantastic work to carry out. So I looked for some kind of help, grants of some sort. I waited a couple of months, I went to Hasselblad, different Swedish organisations, and one day I read in the French Liberation obituaries' section that Jarl Kulle - one of Bergman’s lead actors - had died. I suddenly realized that if I waited any longer I would see them all pass away and still be sitting in Paris! So I kicked my butt and asked a few friends who had connections in Stockholm and found a young woman who had a big flat where I could rent a small room there and so I rushed to Stockholm to start the work. The only contact I really had with the team was through Erland Josephson, to whom I had written a few times. I realized that he was also acting as Bergman’s top PR, as well as he was the person Bergman relied on to get rid of undesirable strangers. I stayed two weeks the first time without making much headway.

Luckily I then met Erland Josephson in person and photographed him, which was not easy because he was very suspicious when we started the portrait session. He was looking at me with very dark eyes. At some point I kneeled by Erland’s armchair and mentioned a moment in Fanny and Alexander, Bergman’s last film which he produced and directed himself - a very dear moment with the Grandmother - in this film Erland plays a Rabbi and speaks with his friend after a big dinner. Suddenly Erland opened his eyes and looked at me: ‘You remember this scene?’ he asked. I said of course because this is a magic moment in the film - they are giggling remembering their youth. Suddenly he looked at me as if he was a different person and said ‘ok I will do my best’! So I answered ‘no, I, will do my best’ and we laughed! This moment was key but I did not know then. The second time I returned to Stockholm I had made a print for the theatre and left it in the director’s office where some actors and actresses saw Erland’s portrait and someone said ‘Oh Erland is alive, we thought he was ill!’ [laughs] This was the second important moment. I realized that Erland was speaking quite often with Bergman on the phone, and I knew I would never ask him to introduce me to Bergman, so as to not place him in an awkward position.

DAVID: How long did this immersion in the troupe last?

BERTIN: Three years! I felt like a fish in the sea. My hotel room was literally in the other building just next to the Royal Dramatic Theatre. The main theatre is on Strandvagen (the very posh banks) but the artists’ entrance on the side is on Nybrogatan, heading up to a market, and to the church where Bergman’s father used to be a pastor. The only art-deco building in Stockholm, quite massive. On the first floor of the Theatre’s Office there is a hotel-appartment for the artists.

DAVID: That ’s where you had a room?

BERTIN: I had the smallest room without windows, with just a very small shower. That’s where I lived for three years off and on. I went back recently and the owner was moved to see me.

DAVID: Do you remember the first time you saw Bergman?

BERTIN: The first time I was waiting for an actress to be available so I could take her portrait. Bergman was rehearsing Mary Stuart by Schiller, one of his last plays and all the actors were rehearsing with Bergman at this time. So they were coming down to pose for me and then were going back upstairs to rehearse with Bergman. So Bergman started to hear a lot about me as well - this crazy French photographer who was photographing all the team! [laughs]

DAVID: So do I understand right, Bergman had not even given you any approval for this project?

BERTIN: Absolutely, he had not even acknowledged me! Suddenly I heard a very slow and elegant noise of someone stepping down the staircase. And then he made his turn, and I started to see the shoes and the body. And I started to see it was Ingmar Bergman. I was about ten meters away from the staircase. All I did was raise my hand saying ‘hey’, he waved back. His body language meant something like ‘thank you for letting me go back home without bugging me’. This started to build my relationship with him. But this was not easy, as I knew that the best photographers in the world had failed trying to photograph him, be it Richard Avedon or Helmut Newton, they had all failed.

I had heard everything and anything about him. The most charming stories and others which would freeze your blood. But when I do a portrait I am not there to be judgmental. I was in Stockholm to photograph him.

DAVID: Throughout your proximity to Bergman, his troupe and the man himself - I suppose you saw him direct, talk, move, throughout the years that you spent there: was there something that you found unexpected compared to your initial personal projections of who the man was? Anything that disturbed your original vision of the man?

BERTIN: I will answer by a little joke. After a horse-riding accident, nothing can shake or shock me anymore. No, I was not in Stockholm to be shocked or be shaken by Bergman, I was in Stockholm to take his portrait.

DAVID: Did you feel there was anything in him that ressembled you?

BERTIN: Really, I never thought about this and honestly I would think too much of myself.

DAVID: In your personal relationships, would you say that you are more on a quest towards Affinity or Otherness?

BERTIN: I know that with Marie, my wife, it is affinity. It just happened, we were not looking for this. When you have to make a portrait however, you do not necessarily have affinity or dislike before you take the picture. I am trying to have absolutely no judgement about the women or men that I am going to photograph. This was not always easy when working with Vogue - where everyone already had a preconceived idea of what to achieve. I want to be a virgin when I meet someone for the first time. When I take a picture I am not on a boxing ring - I do not like this sport - my ego is out of the way. All that is important is the man or woman whom I am going to photograph. I want them to be at ease, I take a lot of time to ensure they are at peace - which is challenging in stressful places such as Paris, London or New York, most people arrive stressed. I spend half an hour to relax them, like dancers, we do breathing exercises and suddenly their bodies and backs are more straight.

DAVID: You did not do that with Bergman?

BERTIN: No no no [Laughs] - when he arrived he was like a sun.

DAVID: Where was that?

BERTIN: In one of the rooms of the theatre. A couple of minutes before the session took place he had learned that the budget for one of his upcoming movies had just been approved. When he entered the room his presence filled the room! He said ‘I can not speak French with you but I can read Moliere in the text.’ By that, he really meant ‘I know exactly where you live’ (I live by the Comedie Francaise in Paris, the house of Moliere). Then he asked me ‘Frederick, what do you call in your own language, the last balcony in the theatre, the upper balcony?’ I had the word on my tongue and I said ‘Le Paradis’ - and I know that Bergman had heard about he conversation I had a year earlier with one of his actors - who knew that Les Enfants du Paradis by Marcel Carne was my favourite film. And he answered me with this strong Paris accent ‘Ah oui, Les Enfants du Paradis!’. And now I had to make the portrait: I had in front of me the man I had spent five years chasing, two years in Paris, three years in Stockholm. And there it is, you have to make the portrait of your life! The tripod was ready, the camera was ready, and then Bergman sat on the chair just where the light was the best in the room. He told me about his childhood and his father who was living up the street preaching in the church. And, suddenly, he looked at me with this little smile, it struck me and I pressed the trigger, it was magic - the noise of the mirror of the camera just increased the magic. As I said earlier, mirrors have never scared Bergman [laughs] - then the intensity of his presence diminished, and he vanished, literally. I was left alone in the room still not realizing if it was a dream or reality. Twenty absolutely amazing minutes. I did not take more than one photo that day, but it was a very good picture. I pressed the button twelve times in total, but only once did I capture this intensity.

DAVID: Well, he posed for you didn’t he? [Smile]

BERTIN: Yes he did. Usually I have to work to get the pose.

DAVID: He knew that you would catch it.

BERTIN: Yes, It was very kind of him because I am usually very deliberate.

DAVID: Was that the camera given to you by your father?

BERTIN: Yes, for the Bergman portrait I took that one.

DAVID: The process of self-examination is central in Bergman’s movies. The possibility of overcoming this self-examination and being, somehow, reborn. The mirror is a recurrent object in Bergman’s movies. In our conversation with Matthew Modine he also mentioned ‘The Man in The Mirror’ by Michael Jackson. That we have to impulse change starting with the man in the mirror. Do you often look at yourself in the mirror?

BERTIN: I never thought I was very photogenic untill my wife started making portraits of me! [laughs] - I have tried to avoid my face for a long time. As Churchill said when you are five years old your face is the one that your parents gave you, but at 35 or 40, you have the face that you deserve, and I think that is pretty true. I do not observe myself much, no. I like to observe the world and everybody around me, since I have been a child, even a baby, but not myself, no. Maybe this is why my portraits are strong, they are not a reflection of me.

DAVID: What traits of character do you value most in others?

BERTIN: Wow, this is an amazing question. The thing you see, is that I am always a photographer, and I always look at people in the street or in restaurants asking myself what I would do if they were posing for me. I look for an elegance, inside and outside people, a simple elegance is what I am looking for. I am not looking for noise.

DAVID: No noise. This is obvious from the type of subject matters you have chosen: you spent time inside Cambridge, inside a theatre, in a Benedictines’ convent…And then in that Lord Byron garden in Sintra, Portugal (You were awarded the Hasselblad World Master Award for these amazing photographs of plants by the way!)

BERTIN: That is true. I do not like noise - and I can also understand people who do not speak. For instance when I photographed Erland the first time, it was made clear to me that I should not ask him for access to Bergman, even though he did not verbalize this specifically.

DAVID: At some point after all these years in the troop and not seeing the opportunity coming to snap Bergman, did you ever think that you would fail?

BERTIN: I did end-up thinking that this would never happen. I was devastated. After one late evening walking through the city I was mulling things over, and on my way back to the hotel, someone from the bar of the theatre which was on the ground floor waved at me, asking me to join them. I entered the bar and of course I tried to hide my sadness. I tried to be joyful, I sat with the actors and the technicians to enjoy one last drink. That’s when I was introduced to a young man who was a student and had Bergman as a teacher. I must say I was a bit filled with envy that this kid could see Bergman every day, and I told him so. And the kid asked me how it could be possible to admire Bergman, an old grumpy man. This young man was very disparaging, to me what he said was simply unbelievable. So, as we say in French ‘mustard got to my nose’. [laughs]. Here you had a young man who was not realizing his luck! Kurosawa, Scorsese, Fellini, Truffaut, Spielberg…All would have killed to have the seat of this apprentice. So I told him how spoiled he was to have Bergman as teacher a man that all the best cinematographers and directors in the world would have traded their own name to be there in that classroom. At that moment everyone in the bar stood still, listening to what I was telling this man, staring at us. And next to us was the poster of the last play that Bergman directed ‘Mary Stuart’- I had been invited to the Premiere a few days back - and he had been acknowledging how amazing all his troupe was! After a few minutes I said to the young man ‘well, anyways, if you still think this of Bergman, no one will change your mind and you will live in an obscure world’. It was getting late, and as I stood up to leave, just behind me, standing by a pillar was one of the prop directors of the theatre. He gave me a big smile and a wink: ’These kids will never know anything’ I said. I then waved at everyone and went back to my room. The next day, I received a handwritten note at the hotel in my letterbox, from Ingmar Bergman himself which read: ‘It is next week’. I will never know if there is a connection to the bar episode I just told you, and really don’t want to know. This is the way it happened.

DAVID: With all the hindsight, do you know what you had been after, what was this quest for Bergman all about?

BERTIN: It is my life. I decided to be a photographer and to build up my work, stone by stone. I never looked at this work as a career, it is more than that, it is a life. I am a photographer, it is my work! I am a photographer in the shower, in the street, even if I don’t necessarily take pictures. I think Bergman was a part of a larger work that I am building every day but I dont believe that I was seeking something specific with him. Every place and community I photographed I realize were very secular places: Cambridge is about a college, a small community, it is like a small country with its codes, rules, flags, laws, and the same for the benedictines, it is a religious community, it is a closed space with its rules, laws, same as with the Bergman troop. Even Lord Byron’s garden in Sintra is a closed place with limited access; where people must obey internal rules. I lived several months with the Benedictines; during one month I was the only guest, which had never happened before; during this week, for security reasons I was handed all the keys of the property, some large keys from the 12th century - one of them was larger than you computer screen! - to open the pont-levis, the main exit of the sanctuary - as we were locked in from six o’clock in the morning to five o’clock in the afternoon. For me it was part of the game. The nuns trusted me and that was a remarkable experience. Two things were not allowed, to attend their meals or go inside their cells. But I saw were they were taking their meals. I shared all their daily lives!

DAVID: What did you take away from this experience?

BERTIN: Something profoundly moving as they posed for me with lots of presence.

DAVID: You ask a lot from your subjects don’t you? When you ask them to pose, you direct?

BERTIN: Well, when I started photography I was an assitant to several photographers and from Harry Meerson I learned to capture the right look with the Giconda effect, so that the portrayed subject looks at you wherever you are standing in the room. The height is important and where exactly the subject must look to render this effect matters too. Some people sometimes ask me to just capture them ‘on the fly’, without posing because according to them 'that is how they look the best'. But my process is different. I want people to pose to actually deliver something much different from a live capture, closer to the actual truth of that person. For Cartier Bresson of course ‘on the fly’ means something, but I do not know how to do this. And I am not interested in this. I like to give the person some time to drop his or her mask. I am not interested in psychology. Often, by looking at the portraits of someone I then understand the person; however, as I am in the midst of working I do not understand anything about the person, and am not interested to understand. I just want to feel the full presence of the person. I am not a big fan of manipulation. There is a great portrait of the German industrialist Alfred Krupp by Arnold Newman where his eyebrows look like the devil’s horns (Alfred Krupp made most of his fortune collaborating with the Nazis during the holocaust); that’s a brilliant portrait that will remain in history, but that is not what I do. Let me tell you another anecdote: the portrait I did of Max von Sydow, in which he looks very mischievous, took me a long time to achieve: I worked with a level, and I had a serious issue with the wall behind Max, I really could not figure out the right horizontal line (at the time we did not have the ability to rework these aspects in post-production); suddenly as I was in the corridor of the Bristol Hotel a bellboy arrived with a huge breakfast tray; without thinking I took my tripod and Hasselblad off the ground to let him go by, thinking that I would have to redo it all! And as I put the tripod back very slowly on the floor, I looked inside the visor and the lines were perfectly aligned!

DAVID: An angel passed.

BERTIN: Yes an angel passed. It made Max laugh a lot! So not only did the alignment suddenly get perfect, a sort of joy suddenly exuded from Max's eyes.

DAVID: You see, ‘every path is the right path’ [laughs] - To me this might summarize what is at stake behind your quest. It seems to me clear that all you have been doing has been to deserve the trust of your mother. And this bellboy is like your mother, who you thought was giving you such a hard time trying to dissuade you to be a photographer. What you thought was initially a curse turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Your mother pushed you to give your best to deserve her trust. You thought it would result in a disaster, when in reality this bellboy came to help you!

BERTIN: Absolutely, and also you have to use in life what is not necessarily positive. My eye problems were not necessarily a blessing at first, but I used this as a starting point to build my life. First you could be angry about things that happen to you. But to use them as something positive, I think that is what is the lesson my father taught me.

DAVID: It is about transmutation, Sartre, ‘life is not what happens to us but what we do with what happens to us’...

BERTIN: Totally. Look at the chaos the world is living through, take for instance terrorism: what these people are trying to do will result in the contrary - as is often the case with some political decisions. And the response I think will not necessarily come from us.

DAVID: From the Middle-East?

BERTIN: Yes. Now maybe this is not something that we will see. For now it is very painful, we have not much foresight.

DAVID: Is there one cause in the world that you would like to address, using your talent?

BERTIN: There is a British war photographer I have been admiring since my early childhood, Don McCullin, who has also done some beautiful landscapes and some heavy clouds. Even through his landscape works we imagine the war scenes he must have endured in his life as a photographer. He had done a portrait of a small child in Biafra in the years 67-70, I must have been very young, maybe seven years old, and this photo had really shocked me; this child must have been my age and he was the size of McCullin's Nikon F. Some war photographers have moved me a lot. The very first war photography is devastating, it is a nurse who is giving water to an injured man on the battlefiled in Solferino. My childhood was marked by the Vietnam war and the LIFE photos, Vietnam being one of the most covered wars in the world, these photographers were quite incredible. So there is this, I admire these photographers risking their lives to show the raw reality of the world. Ansel Adams compares the photographer and the painter. When the photographer works he cannot alter what is in front of him, all he sees is going to appear on the image, whereas a painter is not obliged to include something that bothers him. And digital photography is now making Ansel Adams statement incorrect. You can now get rid of what bothers you. In fashion this has reached its paroxysm. What is formidable with nature is that it is beautiful, at least most of it, and as Bergson said, that it is understandable, and I think that nature is much prettier than the retouched pictures that fashion is showing us. This is why even though I would have loved to be a fashion photographer in the past, today this would not excite me anymore, when each defect must be suppressed. It is the imperfections that make us attractive and different.

DAVID: As if flat were better, we have still not accepted that the earth is round….

BERTIN: Yes [laughs] - but this is changing again, I heard that some people say it is flat again [laughs], poor Christopher Columbus! [laughs]

DAVID: What’s your guiding creative principle?

BERTIN: Coming back to Gustave Pimienta (the famous sculptor) he told me once, ‘a tool too much equals one more mistake’ (‘Un outil de trop est une erreur de plus’). When Bergman makes Sommarlek with minimal means he makes a work of art. In comparison, The Egg of the Serpent, produced with huge financial means, was mediocre. ‘A tool too much equals one more mistake’. This stayed with me all a long time, it is true. To chose your tool in the necessity of the instant. We have to be wary of being too spoiled, we can do things with a minimum of means. Today people are lost in the possibilities and so many available tools. We were lucky - I say lucky - with argentic photography, that we had very few means at our disposal and so we had to deal with that fact and find our path. One day a woman came to a friend selling the twenty four books of the Encyclopedia Universalis telling him that there was ‘everything’ in it. My friend was not interested but did not know how to get rid of her. I said there might be ‘everything’ but the most important is missing. What’s essential is life, the look from the other, the exchange, sharing, a ray of light on an autumn leave, all that life teaches us and that is not in the books. What matters is to know how to catch a look, a grain of skin: I was struck when Gunnard Fisher was talking to me about his lead actress. He told me that her skin was attracting the light and reflecting the light perfectly, any light. Well, Renoir was using the same words to talk about his muse Gabrielle, one century before! That is why I love my job ou see. Without knowing each other, we are in agreement with Renoir, Gunnard Fischer, or Cezanne painting a naked body. I would have loved to meet Renoir or Cezanne, alas it is not possible. The ballet scene and the lighting in Sommarlek reminds us of Degas, and Gunnard told me that he did not know this painter when he did the movie! It is only after that he heard of Degas, went to the Louvre to see by himself, and he was stunned. They felt the same things capturing these dancers, they were in agreement, doing the same job, not knowing each other. That is why they are brothers. I find this remarkable. This is what makes life beautiful.

DAVID: You feel connected to this Family…

BERTIN: Totally, it goes beyond photography. I hope that I am worthy of it! But I am trying to, every day. What matters is to do things with others. I very much like America for this, we live together more. In New York, which I am discovering every day, I am always looking up in the streets, and several times people have stopped me thinking that I was lost [laughs]. In spite of the massive scale of everything there is still an attention paid to the other. I am not necessarily an optimistic person however I believe that my work is. My work is there to say that the world is beautiful, this world is gorgeous. Every human should be forced to do a morning walk to reach the top of a mountain. You must deserve the top of that hill, to contemplate the beauty of the world, this is the result of an effort.

DAVID: Are you happy today?

BERTIN: Yes. happiness has a name, it is Marie. And I love our two cats. I am also happy to see real artists working simply, people who have passion and do extraordinary things, sometimes without even knowing it. This touches me a lot. This winter we got tickets to hear some Gregorian chants at Notre-Dame in Paris, it was really extraordinary. No instruments, only using the acoustics of the cathedral. No one talks about these things, even though it was absolutely wonderful and we will have astonishing memories for the rest of our lives.

DAVID: Did you ever know if Bergman liked your portrait?

BERTIN: I never knew. If he did not refuse it, it means he liked it. With Bergmann we should not expect too much of a show of emotions!

DAVID: What are your favourite Bergman’s movies?

BERTIN: Sommarlek, Sawdust and Tinsel and of course Cries and Whispers. To me Sommarlek is divine. But I must say it is very difficult to pick just one. There is nothing to throw away.

DAVID: It is really as if Bergmann had lived three lives in one, right?

BERTIN: That’s really exactly that. And these scripts! As much as Kubrick was a great director, he did not write the original stories of his movies... but Bergman does it all: he writes the full book, then the script and then he directs the film! This is absolutely magnificent!

DAVID: It is interesting because I re-discovered Bergman recently, and obviously we understand things with life that we would not have understood when we were younger.

BERTIN: Absolutely, it is like Saint-Exupery’s Little Prince, in Japan this book is given to twenty year old students to read. Few people realize that The Little Prince was written by Saint-Exupery in New York to let the Americans know that we really needed their help. And Saint-Exupery was smart enough to write a positive story. The forward is dedicated to his close friend Leon Werth, a Communist Jew. This was not decided randomly. When the Prince asks the pilot to draw him a sheep, he draws a sheep but the little Prince does not like it, so the pilot designs a box. In fact the Little Prince is asking the Pilot to draw him France, and the sheep is the poor French people being assaulted by the occupiers. The French people are in a box. It is also an allegory for all the wagons leaving France carrying Jews towards Auschwitz. That is what this is all about. I really love Saint-Exupery as a man and as a writer. Saint-Exupery believed in friendship, it was something strong and noble at the time. When a friend had problems we were going to help him even in the midst of death. Very few people would be capable of this today. He was an incredible writer and a wonderful leader: his work as a manager of the Port Juby airfield in the Sahara desert was remarkable, very few people know about this part of his life. His duties included negotiating the safe release of downed fliers taken hostage by hostile Moors (a perilous task which earned him his first Legion d’honneur from the French Government). His Notebooks is something incredible to read. Saint-Exupery is someone important in my life.

DAVID: Is there someone else you have in mind as important to you as Bergman, whom you would like to portray?

BERTIN: This would be difficult to choose. What attracts me more is a work in France or Japan on all these craftsmen and artists who are exceptional in their own fields. For instance French landscape designer Louis Benech, whom I met recently. Someone like Guy Martin at Le Grand Vefour, all these giant artists or scientists who, in groups or alone, do their jobs with passion every day, yet who are often forgotten. I really do not know how to approach them but these are the people now who fascinate me most. Civilization will owe them. What Louis does with nature, what Guy Martin does with flavours…This is civilisation. And we have to show these people that what they do is worthwhile!

DAVID: Yes this is important, as we often like to say ‘Do we exist if no one is watching’? [smile] Thank you, Frederick-Edwin Bertin.

BERTIN: Thank you Florian!

For more on Frederick-Edwin Bertin, you may check his website.

Add a comment