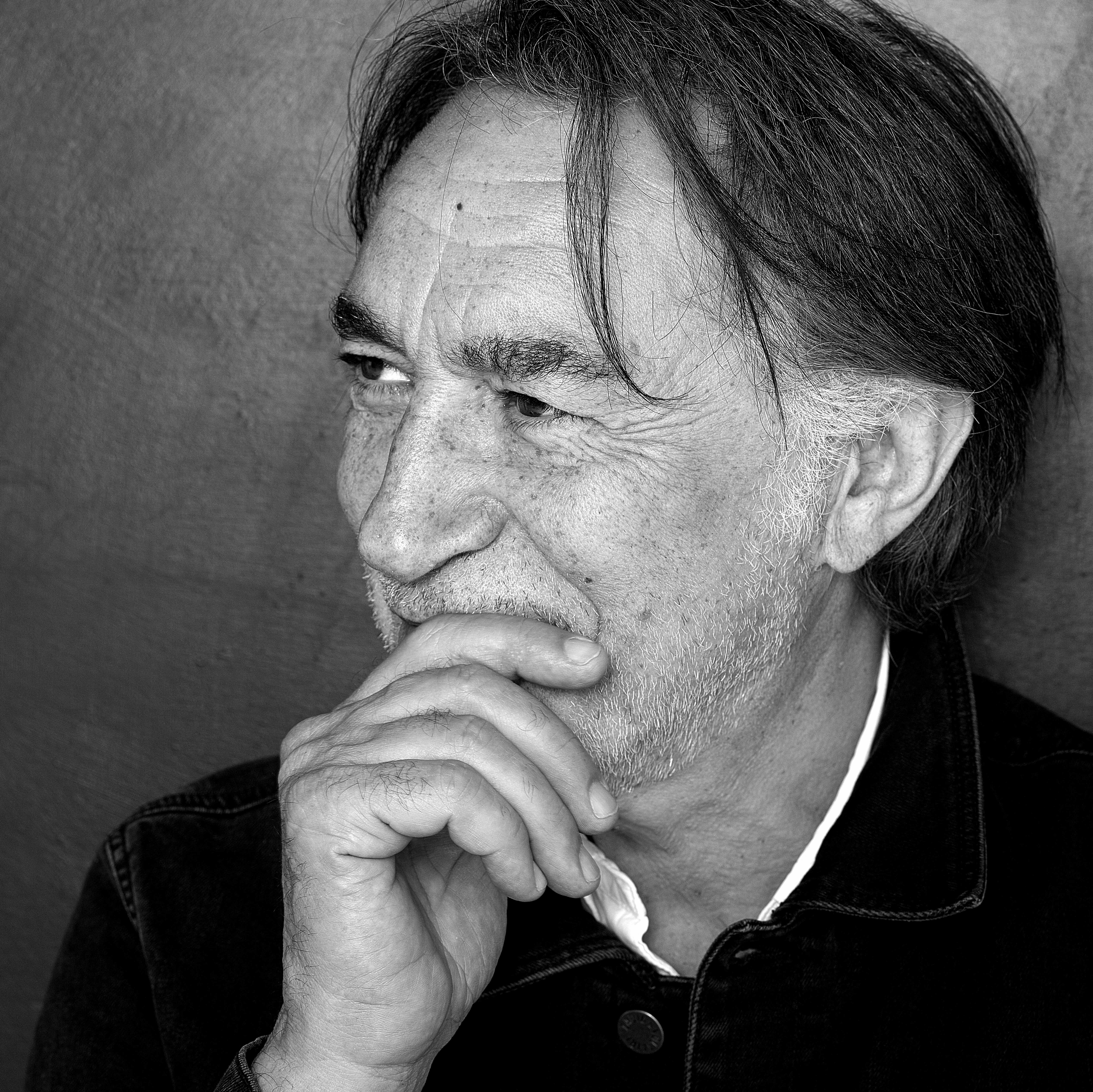

Photography by CELINE NIESZAWER (All Rights Reserved.)

Richard Berry is a French actor, film director and screenwriter. He has appeared in more than 100 films since 1972.

Florian DAVID: Richard Berry Thank you so much for taking the time to engage with us, it is a true honour and a joy to welcome you.

I just finished watching ‘Me Cesar, ten and a half year old, four and a half feet tall’ (‘Moi Cesar, dix ans 1/2, 1,39 m') a movie that you directed about a mischevious kid with boundless imagination and energy, who is trying to understand his place in the world and the grown-ups around him. You were quite energetic yourself as a kid, weren’t you?

'THIS CURIOSITY LED ME TO WANT TO PENETRATE THE WORLD OF GROWN-UPS THAT WAS FORBIDDEN TO ME.'

Richard BERRY: Yes I was born like this! I have been like this for as long as I can recollect and that is also what my parents tell me; I have always been a hyperactive kid but in my time this character trait was very badly diagnosed and people did not know how to treat this, so I was given pills to calm me down! People at the time were only focusing on the over-abundance of physical energy when in fact hyperactivity is first and foremost linked to an intense cerebral activity. I needed to do several things at the same time, I was not able to focus on just one thing as many other children do, my curiosity was insatiable. This curiosity led me to want to penetrate the world of grown-ups that was forbidden to me; it is well known that young kids are never allowed to cross that door and take part in the world of grown-ups. So that’s what this movie is about and I tried to see things through the eyes of the children. I thought that it could comfort some kids out-there who do feel excluded in this way, but also address the grown-ups who do not want to let their kids participate, take part in their adult lives and initiatives, and who because of this are going to see their kids develop these types of mental disorders as is seen in the film: Cesar’s boundless imagination pushes him to come up with some insane stories, for instance persuaded that his father was sent to jail when he was only away on a business-trip!

DAVID: Who wrote this script?

BERRY: It was me originally then we co-developped it with Eric Assous, a co-author with whom I still work.

DAVID: A very effective casting, including the young and talented Jules Sitruk.

BERRY: Yes and my daughter Josephine too!

DAVID: Yes she plays the little girl Sarah Delgado!

BERRY: Yes 'the prettiest girl in the school’! [Laughs]

DAVID: When I say ‘Childhood’ what is the one memory from that childhood that springs to mind immediately? If I ask you to not think too long, the very first thing?

BERRY: I immediately think of separation. My parents were working as sales representatives and were always on the road. That’s something I never recovered from, a trauma; then later on I understood how and why this trauma came about: My father was actually suffering a lot from this situation and he naturally passed on this anxiety to me. So I felt a profound isolation and abandon; also I felt as if everyone was trying to take advantage of me when my parents were not around. Lots of suffering. That’s what I remember when I think of my childhood. And I remember the desire to do things that we are not allowed to do, and the desire to exist while we are being prevented from existing.

DAVID: So you are saying that your anxiety was passed onto you from your dad?

BERRY: I do think so yes. He was suffering from that separation from me, then from my sister. I look at him today and I can see how he is just like me.

DAVID: I saw him, he looks beautiful! You also look alike a lot, in fact you seem to be looking like him more and more as time goes by.

BERRY: Yes, well, If that’s what I am going to look like I am very happy about this! [laughs]

DAVID: Is that what brought you to the works of renowned French Pediatrician and Psycho-Analyst Françoise Dolto? Is that not a bit unusual for a man?

BERRY: Precisely yes, this understanding of education is not a field restricted to women; I read and re-read all Francoise Dolto’s writings so as to behave in the best way possible with my kids. I wanted to make the least mistakes. I did my best anyways. You still make mistakes, but I thought that this could help me un-nod certain situations that are created over time, and to not pass onto my kids the burden of my own anxieties.

DAVID: Françoise’s mother was depressive and was blaming Françoise for the death of her sister (accusing Françoise of not having been praying hard enough!) : Abusive parents often blame their children for their own suffering, shortfalls and self-hatred. Self-hatred seems to be the cause of many of our worlds’ tragedies. Before asking people to love others I think that we first ought maybe to teach them to love themselves no? What is your view on this, and how have you experienced that territory as a parent?

'I THINK THAT WE CARRY INSIDE OURSELVES OUR WORST ENNEMY.'

BERRY: Absolutely. It is hugely important to love yourself. I think that it is the foundation of everything! I think that we carry inside ourselves our worst enemy. I remember that when I started to want to understand better who I was, my anxieties etc…One of the first things that my psycho-analyst made me realize was that an antisemitic man was actually living quietly inside me, and so when I asked her what I should be doing about this she in turn asked me: what would you do confronted with an antisemite?

DAVID: That’s a tough question.

BERRY: Yes, as there are different forms of antisemitism. But as far as I am concerned, since I was born right after world-war two, in 1950, for me antisemitism is associated with Nazism and the Shoah you see. So I answered my psychoanalyst: ‘what I would do’ I said ‘I would kill him’. So she looked at me and smiled. That’s what this is about, this is excatly what you are saying. We have to understand that we are often our worst enemy and we have to silence this inner-enemy. The only way to resolve that conflict is to love ourselves.

DAVID: That’s something quite shocking to hear. Where did this self-hatred come from? Was that this Jewishness as defined by Sartre, the one that antisemites actually create and its negative portrayals of theirs sent back to you, which haunted you and caused a sort of guilt or shame in you? Or the internalisation of a historic necessity to always have had to flee and hide?

BERRY: No, I dont think it had anything to do with that. I think that some level of self-hatred is rooted in each and every one of us. I think that it simply takes the colour of your culture and of your personal history. There is shame and internal conflicts connected to each and everyone’s cultural background. I dont think that Jews are an exception.

DAVID: That’s a fascinating point of view. When life throws blows at you, where do you go and find the strength to overcome them? Our readers may not know that you gave one of your kidneys to save your sister Mary’s life. This of course has been depicted in the French media as a generous act of courage, which it is. But at the time when this happened, I suppose that this was first and foremost an earthquake in your lives, a real life challenge no?

I THOUGHT 'I AM GOING TO FALL ASLEEP' - I REMEMBER THAT MOMENT VERY WELL - 'IT MAY BE THE LAST TIME...GOODBYE!'

BERRY: I don’t think that I found any particular strength. I felt that I did not have any other options really. When you have been growing up in this context, with this handicap and this pain close to you, I felt as if I had always known my sister ill. Because she has an orphan disease condition and there is no cure to it, the only way to save her was to do this transplant or she would have died. My mother first had given her one of her kidneys, and so it was normal for me to do it too. I could not do any other way. I told myself that this was fate, that it was the way it was. I thought: 'I am going to fall asleep’ - I remember that moment very well - ‘It may be the last time…Goodbye!'. But I feel that it did prepare me very well to death. Let’s say that this is a first good step towards death [laughs].

DAVID: You came very close to death indeed.

BERRY: Yes, and that’s what is interesting: when you are very ill, the possibility of death seems logical, but as far as I was concerned I was in top shape, so it was something that I could have decided to not do. But I wanted to save her, for me it was unbearable to see her in that permanent state of pain and suffering. It was somehow as if I was going to repair a certain form of injustice. As if I had been given everything, a good health, the ability to succeed, work, and that she would not be getting any of this. So I shared.

DAVID: That is beautiful.

BERRY: I shared my bottle of water [laughs].

DAVID: And that is something that one cannot repay…

BERRY: That is the way it is, she has absolutely nothing to repay. We live very well like this together. It has been eleven years now, it has provided her with a lot more comfort in her life.

DAVID: It is truly wonderful.

BERRY: Yes, it is well deserved.

DAVID: Let’s talk a bit about the state of French society. In 1995 French Director Mathieu Kassovitz released in France an award winning movie co-written with Said Taghmaoui untitled ‘LA HAINE’ (‘Hatred’) which portrayed three friends from the French suburbs of Paris seeking revenge after one of theirs was killed by the police. A scary portrayal depicting these suburbs as a ticking time-bomb fuelled by frustration, anger and violence. The opening voice over says ‘This is the story of a society that is falling, repeating to itself during its fall to reassure itself: '‘For the time being everything is all right’…'But it is not the fall that matters, it is the landing’'.

Let’s fast forward twenty years. You are directing a movie about the kidnapping, torture and assassination in 2006 of a young Frenchman, Ilan Halimi by a Paris suburbs gang of twenty people. An antisemitic tragedy titled ‘Everything Now’ / ’Tout, tout de Suite’ adapted from the book by Morgan Sportes. Ilan would have turned 34 in five days. This killing ten years ago marked the beginning of a long list of increasingly violent antisemitic murders including that of Jewish children killed at gunpoint in 2012 in Toulouse.

Question: when precisely did you decide to make that film, and what triggered the actual decision?

BERRY: What is interesting is that when this tragic event took place I did think that it was horrible of course, but I must confess that like many people I did not immediately grasp all the evolutions of the world in which I lived and the causes that would push some individuals to committ this type of exactions. The only thing I grasped what that there was still a form of antisemitism that led to this violence, but I did not immediately measure the societal evolution of our country. I am going to answer you on what really prompted me to want to direct such a movie. The reason is that in the wake of the various other subsequent tragedies - in particular the killings in Toulouse - I learned that Morgan Sportes was in the midst of writing a book on the matter - and I knew Morgan Sportes’ writings well from a film I did with Bertrand Tavernier ('L’appat’ / ‘The Bait’) adapted from one of Morgan’s books; I knew that Morgan's views on the matter would be both philosophical and ethological, and that it would also be informed by a very rich journalistic approach including a lot of police documentation. So I thought this is an opportunity to put in prospective this specific case with all that’s happened over the past ten years, with a view to understanding this shift from a crapulous crime - killing a Jew based on the prejudice that 'Jews have money’ - to the assassination of Jews motivated strictly by an ideology. How has that translation been taking place: from a crime for money to an ideologic crime -

(Let’s say a form of ideology because I’m not even sure this qualifies as an ideology really!). In the second instance, violence is federated through the lens of an islamist motivation, which is something a little more structured. That’s what I was interested in. How and why some individuals in society can start to envision their whole behaviours and lives through the prism of that violence. That’s what I was interested in and what this film shows well: everything was there in germ already; we witness a form of wandering, of cultural and intellectual void that leaves room for anything and everything, be it mere intellectual stupidity but also the stupidity that leads to believe in things such as the islamisation of the world and the spread of sharia law etc. I really think that it all first and foremost starts with this intellectual vacuity, a profound stupidiy. And this shows if you watch my movie.

DAVID: While I am not saying that the story was not covered by the mainstream media, it looks to me that overall the French population remained relatively indifferent to this tragedy - also if you remember the much higher level of emotion and mobilization in the country after the profanation of the Jewish cemetery in Carpentras back in 1990. Shouldn’t these anti-semitic murders have been everyone's concern from the start though? Is it fair to say that the French collective consciousness has had to wait for the attacks on French satiric newspaper Charlie-Hebdo (where 12 people were killed including two policemen and eleven injured) to acknowlege both emotionally and rationally that something was not going right in France?

'I HAD NOT ANTICIPATED THIS SLOW CRUMBLING OF FRENCH SOCIETY.'

BERRY: In fact, even during the Halimi affair there has been thousands of people demonstrating in the streets. I actually decided to replace my film in the historic context because I knew that the future generations would otherwise forget what exactly happened and what was the Halimi Affair. But even this people forget quickly. This is why I have puposely included some real archive footage. This did cause a lot of emotion in the country. What is true however is that I had only perceived this event as a crapulous act, you see, I had not anticipated this slow crumbling of the French society. When you refer to the movie ‘La Haine’ this simply depicted the state of the French suburbs, and similarly in my movie we simply portrayed these kids from Bagneux as delinquants of sort, which was absolutely horrible but that was that (we did not dig much further). Retrospectively, now I do think that it was in fact going way beyond a mere crapulous crime. But we did not see it. Or we did not want to see it.

DAVID: Please correct me if I am wrong: I saw about four books reporting on or analysing Ilan Halimi’s murder. Three authors are Jewish or from Jewish descent (Morgan Sportes’ father was Jewish) and this includes Ruth Halimi’s book (Ilan’s Mother). I did not see many other non-Jew French intellectuals rushing to analyse what happened. Am I right or wrong on this?

BERRY: There has been quite a few books on this, but you are right that there may not have been enough cold, distanciated analyses on what actually happened. To be fair people today are living from one terrible tragedy to the next, and we live in a world where there is always something worse taking place somewhere else...

DAVID: True, yet another banality of evil. Would you say there is an apathy of the French political class?

BERRY: It is not apathetic, it is cowardly. It is electoralist, it is afraid to disappoint a portion of their electorate. They take no risks whatsoever. When in fact I think that the French people today more than ever need politicians who are not apathetic, who take risks and make decisions, even at the risk of shocking. Alas, Holland (The French President) has done the exact opposite of this. He has been driving France without any long-term vision, changing orientation every five minutes, and all with absolute sluggishness. The little reforms he has done don't count, they are totally negligible.

DAVID: Isn’t the lack of courage in politics the worst of plagues?

BERRY: Absolutely, but it is more and more widespread because of the fear of politicians of losing their voters.

DAVID: Election after election lately we have seen commentators and opinion institutes alike express their surprise at the outcomes. Are you concerned that far-right politician Marine Le Pen could actually win this coming presidential election?

BERRY: I think it would be possible, however not this time. But clearly yes, if there is no positive change in the next five years. The simple fact that she may be present at the secound round of the elections is already something huge!

DAVID: Two words: 'civil war’. We read and hear these two words more and more often in the French media, something which would have seemed unthinkable just five years ago. What is your personal assessment of the situation, possible in France?

BERRY: No, no, I think people like to shock and to use extreme words. We see that there is a need for solidarity and togetherness in the face of the dramatic events that we have been living through. I do not see a civil war coming, far from it.

DAVID: If you had the power to be heard now by every single person on the face of our small planet, what is the one thing that you would like to tell them?

BERRY: I dont know, I do not have this pretense. I think that we all have to live day by day, calmly, and improve things daily. Things are not that dark in the end.

DAVID: This is what we can hope for. Let’s pursue alongside some lighter avenues. The film that placed your career into orbit was ‘Mon Premier Amour’ with Anouk Aimée. What a strong, beautifully symbolic title to embark on your journey as an actor! What emotions do you remember from that shoot with Anouk, can you tell us?

BERRY: It was extraordinary yes. I do remember it all like if it were yesterday. For me I was so proud to play the son of Anouk Aimée, she is so beautiful and exceptional I could not understand why they chose me! [laughs] But it is Anouk Aimée herself who fought to impose me in this role. I was every single day inside this emotion and pride of playing her son. And let’s not forget the subject, the story of a son who loses his mother and Elie (Chouraqui) had just lost his mother a few years back in a car accident so I also felt that I was interpreting his pain in a way. Emotionally I felt like I was carrying a lot of weigh. For me it was also the entrance in the world of cinema through the main entrance: I was holding a leading role, and the emotions I was responsible of exuding could not be betrayed, I really felt an obligation of loyalty. A beautiful adventure!

DAVID: Early on in your career you spent seven years at the demanding Comédie Française. What did this teach you about mankind in general and about yourself in particular?

BERRY: First it taught me the difference between a text that is well written and a text that is not. It teaches you to read! [laughs]. I have been lucky to play a large repertoire, which provides you with a large culture and a strength indispensible to an actor. However I do not have only good memories about the Comédie Française. I was not really happpy there. The way it works is not really compatible with the job of an Actor. It had too much to do with people reciprocating favours, and if some administrative rulers liked your face or not, and so I wasn’t very happy about this, I much prefered the violence and the truth of the actual work as an actor, because at least you are chosen amongst everyone without any favouritism and things really depend upon yourself and your own personal talent essentially - not always, but as the general rule.

DAVID: Clearly you did not get where you are due to any favours. You owe your success essentially to yourself. In today’s world many people seek fame and celebrity status as if these were an end-game, without really having the actual craving or talent for the art itself, which is sad. The great George Balanchine said once that he did not want 'people who wanted to dance' but 'people who had to dance'. And that’s all the difference I guess. You need acting in your life as we need breathing right?

BERRY: That’s exactly that yes!

DAVID: I would like to talk about your move from acting to directing. What I would like to know is if that coincided with a different mental perception in your own life, and a desire to also regain control over your personal destiny? What was happening inside Richard Berry’s head during this 'transition’? Was there also a ‘transmutation’ of some sort?

BERRY: It is a mix of these two things. To be totally honest, I embraced at last a dream that I had, a desire of directing that I had had inside of me for a long time, but I was not daring, because I was installed in a comfortable actor’s life, shooting movie after movie. And all is well and we do not ask ourselves any questions. And one day I had a motorbike accident and when I got home from the hospital I sat on the sofa and realized that I could just have died, not be there, and I would not have been doing what I wanted to do. And so the first thing I did was to phone a producer and I told him that I wanted to make a movie based on a book that I had read a little while back. And so I dared to do something that I had been wanting to do for a little while. But it is true that it came as the same time of what you said above: I was craving for independence, for freedom, I had been doing a psychoanalysis for a while and I had become more confident about what I could say, the way that I could tell stories to others, and that’s how my second movie also came about. My bike accident was in 1999, my first movie came out in 2000.

'AND ONE DAY I HAD A MOTORBIKE ACCIDENT AND WHEN I GOT HOME FROM HOSPITAL I SAT ON THE SOFA

AND REALIZED THAT I COULD JUST HAVE DIED, NOT BE THERE,

AND I WOULD NOT HAVE BEEN DOING WHAT I WANTED TO DO.'

DAVID: Is there a particlular period in your life that you have enjoyed most and why?

BERRY: Today I am very happy every single day [laughs]. There has been ups and down, but I have been happy for a few years now. I have everything I need, some wonderful children, a wonderful daughter, a wife whom I love...

DAVID: Richard Berry on love?

BERRY: Listen, I think that I have found some balance in my life at last. It’s all very well to love, but it is also something quite extraordinary to feel loved! This is what I feel now, and this is what I am also craving, it all goes back a bit to your very first question, we can only be truly loved once we love ourselves, and I consider that now I have the right to be loved, and I am claiming that right!

DAVID: How about friendship? It fills a huge place in your life too right?

BERRY: Absolutely, a huge place. An enormous place. It is more and more essential, and by now, with time gone by, when you are my age, you really see who is left. I have extremely dear friends.

DAVID: You are a loyal friend…

BERRY: Yes, but I also have loyal friends. It goes hand-in-hand.

DAVID: What’s a friend to you?

BERRY: I don’t know, It is a bit like in love, it is a bit the same thing you know, it is someone who thinks about you, who is present, with whom you enjoy conversing, sharing, it is also someone who asks how you are, and you want to know how he/she is, and lastly there is something unconditional in friendship, it survives life’s challenges, but also time, we can remain appart for a little while without seeing each other, a friend is someone with whom we can sail through a lot of emotions, someone we are happy to reconvene with, whom we like to think of. That’s what a friend is.

DAVID: Do you have a favourite poem?

BERRY: Yes I do, It is a poem by Louis Aragon ‘Rien n’est jamais acquis a l’homme’ (Nothing is ever definitely granted to Man).

BERRY declaiming the begining of the poem (whole poem below):

Rien n'est jamais acquis à l'homme Ni sa force

Ni sa faiblesse ni son coeur Et quand il croit

Ouvrir ses bras son ombre est celle d'une croix

Et quand il croit serrer son bonheur il le broie

Sa vie est un étrange et douloureux divorce

Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux

Sa vie Elle ressemble à ces soldats sans armes

Qu'on avait habillés pour un autre destin

A quoi peut leur servir de se lever matin

Eux qu'on retrouve au soir désoeuvrés incertains

Dites ces mots Ma vie Et retenez vos larmes

Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux

Mon bel amour mon cher amour ma déchirure

Je te porte dans moi comme un oiseau blessé

Et ceux-là sans savoir nous regardent passer

Répétant après moi les mots que j'ai tressés

Et qui pour tes grands yeux tout aussitôt moururent

Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux

Le temps d'apprendre à vivre il est déjà trop tard

Que pleurent dans la nuit nos coeurs à l'unisson

Ce qu'il faut de malheur pour la moindre chanson

Ce qu'il faut de regrets pour payer un frisson

Ce qu'il faut de sanglots pour un air de guitare

Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux

Il n'y a pas d'amour qui ne soit à douleur

Il n'y a pas d'amour dont on ne soit meurtri

Il n'y a pas d'amour dont on ne soit flétri

Et pas plus que de toi l'amour de la patrie

Il n'y a pas d'amour qui ne vive de pleurs

Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux

Mais c'est notre amour à tous les deux

[English translation]:

Man never truly possesses anything

Neither his strength, nor his weakness, nor his heart

And when he opens his arms his shadow is that of a cross

And when he tries to embrace happiness he crushes it

His life is a strange and painful divorce

There is no happy love

His life resembles those soldiers without weapons

Who have been dressed up for a different fate

Why should they get up in the morning

When night finds them idle, uncertain

Say these words, my Life, and hold back your tears

There is no happy love

My beautiful love, my dear love, my tear

I carry you within me like a wounded bird

And those without knowing watch us pass by

Repeat after me these words I braided together

Which for your big eyes died straight away

There is no happy love

By the time we learn to live it’s already too late

Let our hearts cry in unison at night

How much unhappiness it takes for the least song

How many regrets to pay for a thrill

How many tears for a guitar melody

There is no happy love

There is no love which is not pain

There is no love which does not bruise

There is no love which does not wither

And no greater than you the love for the country

There is no love which does not live from weeping

There is no happy love

But it is our love to the two of us

BERRY: It is beautiful because as we read this poem we think ‘it is terrible’ what he is saying, but the end is beautiful, he ends on these two verses: ‘But it is our love to the two of us’, and so it is a bit everyone’s story, it is difficult, it is complicated, there is the ideal of love and…I also really love ‘The Dormeur du Val’ because I think this is one of the most beautiful poems ever written on war, on the universality of war. I find it very powerful and moving.

DAVID: These are beautiful poems yes. Is there one particular book that moved you he most?

BERRY: It is interesting because it would have to be books dating back to my youth, books by Albert Cohen, at the risk of sounding obsolete, ‘Le Livre de Ma Mère’, ‘Belle du Seigneur’ these are books that have made a really huge impression on me, and then books like ‘A hundred years of solitude’ by Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

DAVID: Chess is a passion of yours, do you still play?

BERRY: I play only occasionally...

DAVID: Would you accept a game against Gary Kasparov, and is there any chance that you could beat him?

BERRY: [Laughs] Of course I’d accept! He would see immediately at the third move, and so would I, that he is going to beat me, however I would not play to win, I’d play to be able to say that I played against Gary Kasparov [Laughs], just for the pleasure of it!

DAVID: Well, pleasure does matter in life!

BERRY: In the end, Richard Berry, philanthropist, or misanthropist?

BERRY: I’d say some days philanthropist and some days misanthropist. But I feel more and more like a misanthropist turning into a philanthropist.

DAVID: Berry is ‘On the path’ towards philanthropy…

BERRY: That’s exactly that. I think that’s the way to go and to behave.

DAVID: Thank you very much Richard Berry.

BERRY: You are most welcome. Thank you very much I really enjoyed this.

Add a comment